Dave Barr (born April 12, 1952 in Los Angeles, California, is an American veteran of the Vietnam War and a motorcyclist best known for being the first double amputee to circumnavigate the globe. He lives in Bodfish, California where he runs a motorcycle tour company. He is also the author of several books and was inducted into the Motorcycle Hall of Fame in 2000.

Barr joined the US Marine Corps when he was 17 and served in Vietnam on a helicopter gunship.[1]: 5 After his discharge from the Marines in 1972 he lived in various locations around the world and served in the armed forces of several countries, including: two years with the Israeli Parachute Regiment and one year Rhodesian Light Infantry. He was in the middle of two years of service as an enlisted army paratrooper with the South African Defence Force,[1]: 5 when he was injured in a land-mine explosion in Angola in 1981.[2] In 1981 while riding in a military vehicle in southern Angola, his vehicle drove over a land mine and the resulting explosion cost him both of his legs,[3] above the knee on the right and below the knee on the left. Prosthetic legs allowed him to complete his tour of duty.

Dave Barr’s Story!

Imagine yourself riding a motorcycle through the shimmering heat of the Sahara Desert. The land and the sky reverberate in one immense echo. The blinding, indifferent sun is your only point of reference, and it would just as soon eat you alive than guide you safely. Water and fuel supplies are finite, you are limited to what reserves are strapped to the bike. There is no road. There is no traction. If you don’t keep your speed up in the deep, drifting sand, you’ll crash. If you make any hasty movement at the handlebar, you’ll crash. Shift your weight—crash. It’s that simple…like life and death wired to a light switch. Would you be able to endure such a challenge? Would you even consider trying?

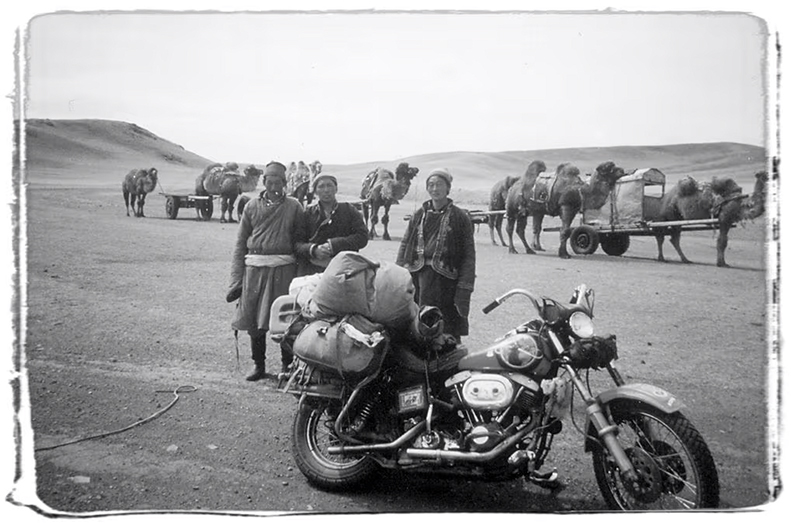

Well then, what if I said the bike you are riding is a 1972 Harley Shovelhead with more than 150,000 miles on the odometer? Do you think you could survive seven flat tires, a high-speed crash and a standoff with sword-wielding nomads in the Sahara? Is anyone out there still intrigued by the dare? If so, add another 83,000 perilous miles until you’ve circled the globe north to south and east to west. You’ll live on that Wide Glide for three-and-a-half years, and you’ll encounter every element and every emotion defined in the human experience.

Now, if there’s anyone still left standing, try to imagine doing it all without your legs.

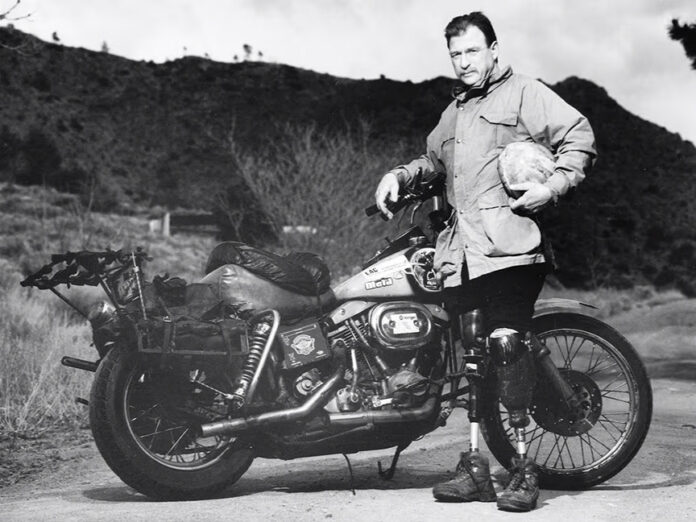

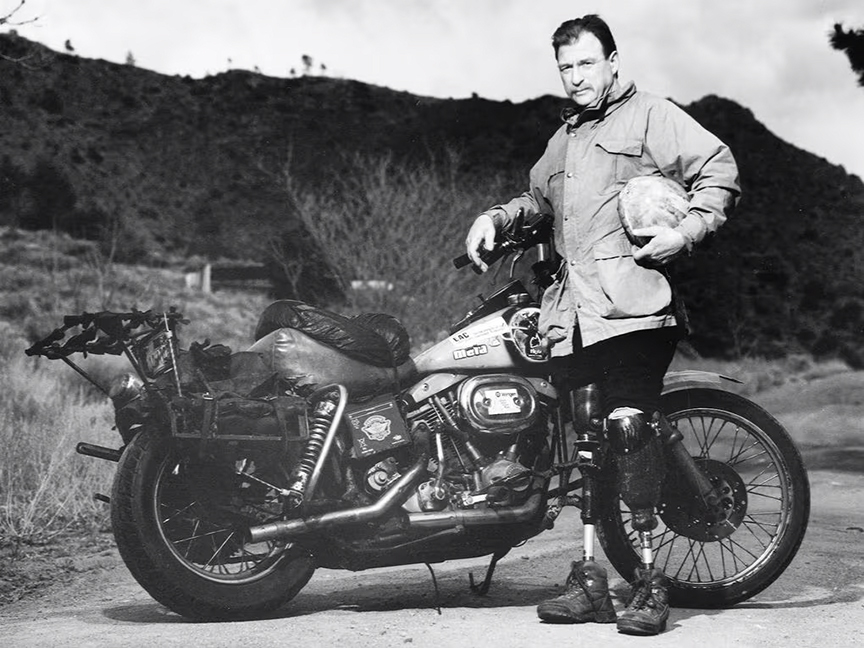

When Dave Barr purchased this Harley-Davidson Shovelhead in 1972 he was fervent with youth. He would lose his legs nine years later, but his passion for living would remain.Photo Courtesy of Dave Barr

Dave Barr is an unusual sort; he’s multilayered. Having breakfast at his home in Bodfish, California, along with his wife Susan, I am taken by how ordinary he seems…and how settled he appears. I expected a gypsy; some road-worn nomad who can’t sit still. This wasn’t the Dave Barr I expected—this unaffected man who raves about his wife’s banana-nut bread, agonizes over crows in the garden and frets if Cleo the cat is out after dark. On the surface he is a common man with simple needs, strong morals and a slow grin. What’s inside is more difficult to decipher.

Barr talks a lot about destiny. He believes we have a choice to either follow it or change it. “You’ve got a destiny and it’s not always going to lead you in a safe direction. It’s very possibly going to lead you into harm’s way—maybe in the business world, maybe socially—there are all kinds of dangers. That’s why most people don’t follow a destiny, they pick one. They pick a safe road.”

The road he saw as his destiny wasn’t always a grueling motorcycle tour around the world. Early on, it seemed his destiny was slated for soldiering. After his childhood in California he enlisted in the Marines. It was 1969 (not a big year for voluntary enlistment) and Dave Barr was 17 years old. His father, a World War II vet, proudly signed the age waiver. To Barr, it felt like something he’d been waiting for his whole life. It certainly wasn’t an easy road, but he found comforts along the way. Commitment and honor were family values that soothed him in the military, as another kid might take comfort in finding bologna sandwiches being served in the college commons.

After Vietnam, Barr returned to a homeland that couldn’t relate to him any more than he could relate to it. He tried settling into a civilian job and the material possessions other Americans found so placating. He also tried bonding with the country physically. He rode 12,000 miles on his ’61 Panhead from Los Angeles to New York and back. It may have been a sign of his future calling, but he didn’t find the sense of belonging he needed at the time.

Muddy roads in Zaire overwhelmed him, but there were always locals to help put the “crazy white man” back on the road.Photo Courtesy of Dave Barr

In 1974 Barr found himself drawn back to the armed forces, but this time in Israel serving a. people whose ideals reflected his own. He served there as a paratrooper for two years before returning again to try and embrace his native country. He still wasn’t ready to call it home. His sense of adventure and taste for military structure led him to the Middle East, then on to Rhodesia, where he served in the Rhodesian Light Infantry. After the liberation he went south and joined the South African Army. It was in South Africa, in 1981, that Dave Barr’s destiny changed.

“I knew when that mine went off nothing was going to be the same,” he says. He was riding in an unarmored vehicle when it contacted a land mine. As bad days go, Barr rates that one a 9.5 on a scale of 1 to 10—10 being death. Badly burned, his lower body mangled, he knew moments after the explosion he’d never be physically whole again. Nine months later he left the dirty military hospital in Pretoria. He had endured twenty major surgeries, four of which were amputations.

His right leg was gone just above the knee and his left leg had been removed just below the knee. When he asked the doctors if he’d ever be able to skydive or ride a motorcycle again with the crushed left foot, they assured him he would not. He opted to sacrifice the useless limb for possible mobility with prosthesis rather than be bound to a wheelchair. After he was released from the hospital, he boldly went back to active duty—repairing weapons on-site for six months in order to finish his tour in South Africa—before returning to the country and family he had walked away from four years earlier.

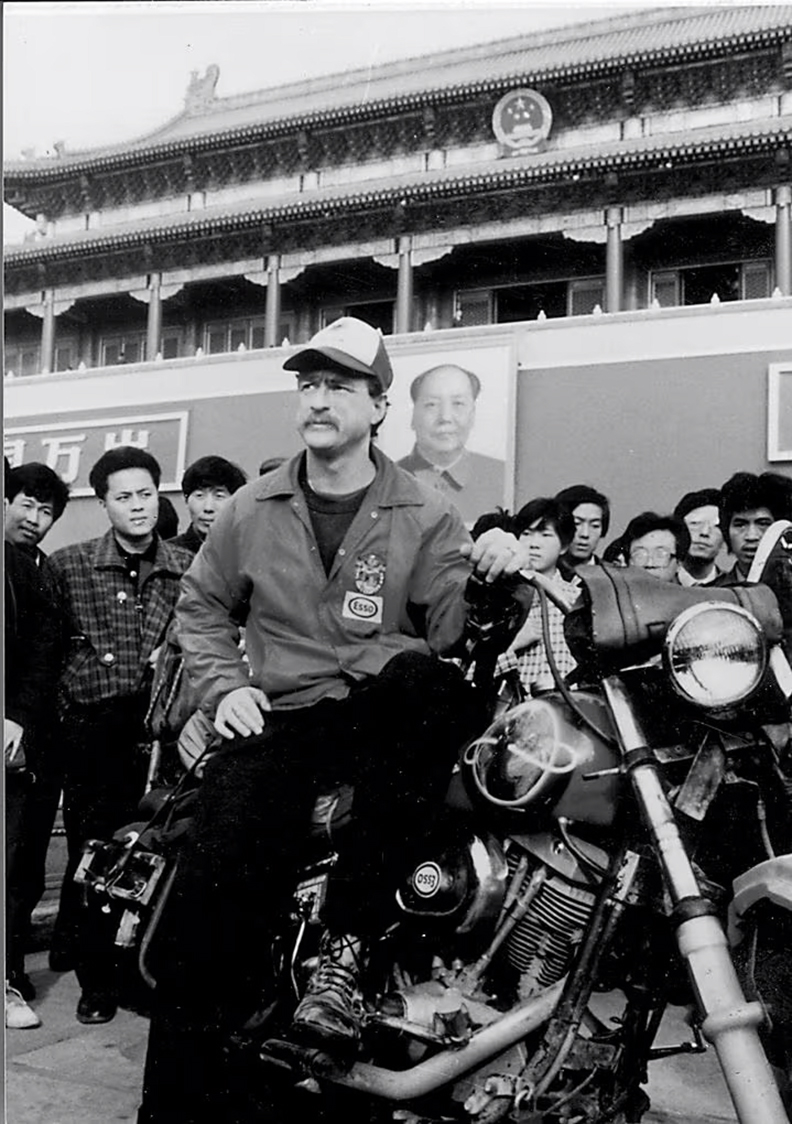

Barr was the first American allowed to bring a motorcycle into the infamous Tiananmen Square in Beijing, China.Photo Courtesy of Dave Barr

“I knew after the mine my focus in life was being shifted. How was I going to spend my life? When you look in a cemetery you can see the date a person was born and the date they died. In between is a dash. You’ve got to make the dash count.”

In 1982, he was reunited with his mother and father in California. Shortly after, he met up with something else he’d been missing, the ’72 Harley Shovelhead he had bought 10 years prior.

“There were two things that were really on my mind: skydiving and motorcycling. I found that I could still dive if I wanted to [Barr has completed 200 jumps as a double amputee] and the next thing was to ride.” He knew he’d never be able to kick the motor over again, so he had an electric starter installed. Next, he and his father devised a brake-pedal plate where his prosthetic foot could rest all the time.

“When I rode that motorcycle for the first time I knew what my long-term goals and destiny would be: to try and ride it around the world.”

Barr did ride that motorcycle around the world, and then some. He tried everything and didn’t let anything stop him. It took three years of tedious preparation and more than three years to complete the trek. The tale is thoughtfully told in his 500-page account, Riding the Edge. The book is about endurance, but not about motorcycle-endurance riding. It is about the ability of the human spirit to endure; taking everything life has to offer and accepting it as necessary for personal and spiritual growth. He never once considered giving up.

“Honor means a lot,” he says. “Once you commit to something you’ve got to give it everything you have.” He cites the Chinese proverb: Fall down seven times, stand up eight. “No one is going to succeed at everything…but you only fail if you quit trying.”

Still, Barr seems superhuman—he was riding a 1972 Harley, for crying out loud. “Yeah, it would have been easier on another motorcycle,” he laughs. “It was a love/hate relationship that boils down to you and this machine and how you’re going to get where you have to go.” The circumstances he describes in Riding the Edge are enough to give common motorcyclists nightmares. “I had some very good training in the military. I learned how to handle pain and fatigue.” But he does not fully credit the armed forces for his stamina. “I also have a tremendous faith in God and I believe that will give us whatever we lack personally.”